Who Art in Heaven… or the Other Place!

I wrote an essay about my late father for a creative writing group I joined in Newcastle-under-Lyme in 2017. It was during a period of time when I was undertaking voluntary work, prior to returning to professional employment. We were set a task to write five hundred words based around the word ‘resolution’. The essay here is based upon stories my father told me about his late childhood / early adulthood.

Probably closer to the truth is that I wrote the article for my late mother, who used to say I was a chip off the old block. 🙂

Essay Start

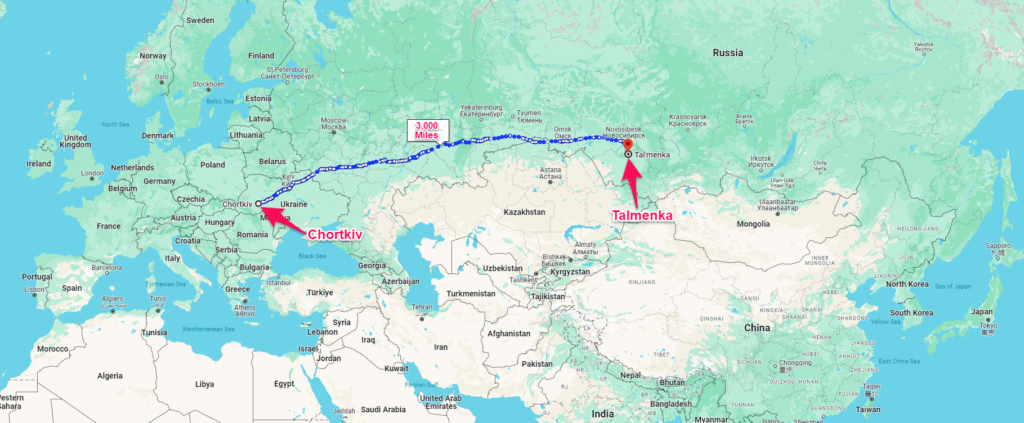

My father, Jozef Wozny, was born in 1928 in the village of Chortkiv in the south-eastern flank of Poland, about 100 miles south-east of Lviv in Ukraine. On 1st September 1939, Nazi Germany invaded his fatherland from the west – triggering Britain to declare war on Germany on 3rd September. On 17th September, when Jozef was eleven, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from nearer to his home in the east. As part of the Soviet de-Polonization policy, on 10th February 1940 Chortkiv village residents were arrested by Soviet soldiers and given thirty minutes notice to prepare to leave. Jozef and his family were then shipped over 6,000km on boxcars (cattle trucks) to a labour camp in Talmenka, Siberia (Russia). The journey took seven weeks on parts of the trans-Siberian railway, where he was surrounded by the dying and deceased; the Soviet soldiers didn’t permit the train to stop to enable the dead to be taken away. Jozef told me that cattle, which the boxcars were intended for, had more dignity than the Poles on their journey to death. Jozef summarised the predicament as “Being shipped off into the cold and bleak unknown – thousands of miles from home, where overseers treated them with contempt.”

After one year in Siberia, Jozef’s elder sister Veronica died at the age of nineteen (Jozef was thirteen), following becoming separated from her family. Soviet authorities recorded that Veronica died of malnutrition. Emelia (my grandmother) wanted visual confirmation that Veronica had indeed died, so she sent Jozef on a six-hour train journey to the mortuary. Jozef clung to rails on the outside of a cattle truck in bitterly cold conditions – seemingly the designated mode of travel for exfiltrated Poles in the Soviet Union. When Jozef arrived at his destination, he’d partially lost consciousness and his hands were frozen to the boxcar; he couldn’t move his limb. He recruited the assistance of a bystander to help snap him away.

Jozef had arrived late at night to the mortuary; there was no lighting, so he needed to feel around the numerous dead bodies until he sensed a birthmark which he knew was on Veronica’s thigh. Jozef was a farm labourer, not a doctor, but the sight of his emaciated sister (she’d likely starved to death, not suffered a fatal illness) confirmed the sad news he’d been sent there to determine. I believe these events demonstrates Jozef’s resolution.

In June 1941, the German Nazis turned their aggression towards the Soviet Union. While withering under the onslaught of Operation Barbarossa, the Soviets released their Polish captives, so that they could fight their now common enemy. At the age of thirteen, my father forged his age to fourteen in an application to join the Polish Free Army (PFA). In addition to wishing to fight the German Nazis, this undertaking was to give his mother one less mouth to feed, since death from starvation would have been the likely outcome for one of her children in late 1941. Jozef’s first posting after joining the PFA was in Palestine, where it might be expected that the most significant changes to his living environment would be the temperature, the desert sand or the sea. Jozef advised me that it certainly wasn’t the case, it was actually that he now had the opportunity to see the horizon. My father said it was by far the biggest adjustment to his life, after living for two years in the depths of horizon free Siberian forests.

Jozef and his immediate family emigrated to the UK after the war. Despite being a gifted verbal communicator, he had poor written English, and appeared content to take unskilled labour positions. Jozef used his oratory skills in representing other Polish immigrants when they had cause to be challenged by authorities over often trivial matters. Jozef was never more passionate than when defending someone he felt had been unfairly treated – he was resolute in their defence.

I’ve attempted to correlate Jozef’s essential qualities to some of my own characteristics. I was determined enough to be successful by many yardstick measures in life, such as those listed here:

- I achieved a first-class university degree

- I held senior professional roles in both the public and private sectors

- I was recognised as an expert in the corporate IT security field by my peers

While the above items are substantial achievements, they don’t evidence my resolution. I’m telling this story in December 2017, as a happy and healthy forty-eight year old. In July 2015 I was injured in a bicycle / car collision, whereby I suffered a Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and was airlifted to a hospital. The critical care doctors advised my mother to expect my imminent death, thereafter initiating the signing of relevant organ donation paperwork. However I remained alive in a comatose for twenty-eight days, before emerging from my coma into a locked-in syndrome state for a week.

In the following four months, I rapidly overcame the clinical limitations resulting from my brain injury and was discharged home from hospital after learning again to walk, and to take a shower / use a toilet without assistance. The really hard part began in earnest when I attempted to get on with living a normal life, as I was still mentally limited in many ways. I used to be a professional high-flyer, but now it seemed that my high-flying was book-ended by a trip in an air ambulance helicopter.

I refused to allow myself to appear miserable, never-mind become depressed; my resolution pricked my conscience into driving me. I knew that my loved ones had been prepared to sacrifice their better lives to care for me with no guarantees (or even likelihood) of a positive outcome. There was never any possibility of allowing myself to become a burden upon them after I’d witnessed their determination to care for me. I’m content I’ve evidenced how bloody-minded I am, or I could put it another way, I’ve demonstrated resolution.

Three years after writing the above essay, I discovered that in 2008 I’d transcribed conversations with my father about some of his wartime experiences.

Random Muses From / About My Father

Funeral Eulogy

My sister, Susan, gave this eulogy at our father’s funeral in May 2016.

Jozef’s Mantra

Whenever my father and I were working together on a task, he wouldn’t contemplate putting anything off for even a day. He used to assert “There is no tomorrow”, it was his mantra for the way approached life tasks. I feel that my father’s doggedness rubbed off on my becoming a purposeful, results-oriented and gainful person.

Humility Begins at Home

When I was sixteen, I was arrested for shoplifting and held in police custody. While collecting me from the police station, my father told me that he’d left my weeping, heartbroken mother at home. My father purposefully explained to me how my mother had given all of her love and support to me, and her reward was that she’d parented a common thief. It was the most knowing way I could imagine to deal with the situation, it completely re-orientated me.

Russian Suspicion

My father always said that Russian citizens were individually as good and bad as those of any other nation. However, he felt that Soviet / Russian politicians were pure evil, personified by Joseph Stalin, who he considered having moral equivalence to Adolf Hitler. My father often associated World War II aggression to Russia, as that was his first-hand experience; he’d seen his sister die due to them, which made it personal. My father recounted how perhaps five million Ukrainians starved to death due to Soviet agricultural policy during World War II, even greater numbers than the murderous plague of Nazis. My father attributed most major post World War II conflict to Soviet influence, such as the Korean and Vietnam wars. He recounted numerous times that on one night in October 1962 during the Cuban missile crisis, he kissed my mother goodnight and told her how much he loved her; this was during the period where a nuclear war, and the likelihood of collateral death, was a distinct possibility.

My father could never understand why the hammer and sickle flag, or the term CCCP (Russian equivalent to Soviet Union – USSR), became trendy in the 1970s in the UK, as my father always associated these emblems with their evil connotations.

While with young friends aged between twelve and fifteen in a Siberian forest, they played hide and seek with a Soviet soldier. The soldier failed to see any humour in the situation, and shot dead one of my father’s friends when he found him. My father stayed hidden under a fallen tree, while the soldier walked across the trunk.

The BBC produced a narrated documentary about Poland, entitled “The Invention of Poland.” Episode 3 was entitled ‘Stalin from the right, Hitler from the left’.

WikiPedia Article

After the invasion of Poland early in World War II, the Soviet Union occupied vast areas of eastern Poland. Allied to the occupation were large-scale forcible deportations of Poles to Siberia, Kazakhstan and other remote areas of the Soviet Union.

Birth Date and Location

My father was born in Chortkiv, Poland on 24th July 1928, about three hundred miles east of Krakow. He spent most of his early childhood in nearby towns by the names of Teklowka and Ivane Puste. Following the Soviet Union’s invasion of Poland during the first month of World War II, this region became part of Ukraine. The arrow on the first map indicates the approximate location of Chortkiv in 2023, the second map shows the portion of Poland (dark green colour) which was incorporated into Ukraine from 1939.

While in Siberia, my father falsified his date of birth on Polish free army application papers, changing it to 13th November 1927, making him eligible to serve as a fourteen-year-old. Despite all of his ensuing identity paperwork such as immigration documents, passports and driving licences, as well as his retirement age / status referring to 13.11.1927, he only mentioned his date of birth to me as 24.07.1928.

My father was demobbed to England and applied to become naturalised, he became a UK citizen in the late 1960s.

Poles / Polaks

My father didn’t return to Poland until visiting in 1977, thirty-eight years after leaving in 1940 as an eleven-year-old. My father took great pride in his Polish ancestry, as I also do.

I’ve always encouraged my daughter to be curious about her Polish heritage. I was delighted when she told me how she takes pride in her heritage, and enjoys the fact that she’s a little different.

When I started work as a seventeen-year-old engineering apprentice, I was given the nickname of ‘cabbage eater’ on account of the basic foodstuffs they patronisingly associated with my Polish ancestry. In defiance of the crude stereotyping, I eat cabbage whenever the opportunity arises. 😀

My father had a good Polish friend named Jo Woch, who in 1944 fought with the Allies’ Polish infantry at the World War II battle of Monte Cassino in Italy (roughly between Naples and Rome). Mr Woch had his right elbow shattered in a gunshot wound, which caused him discomfort for the remainder of his life, and resulted in him wearing a special brace. Regardless, whenever there was building work which required plastering or pointing of cement on outside walls, he was always the person to do it. I recall when I bought my first house, Mr Woch undertook the plastering of my two chimney breasts, and pointing the outside wall which required him to use a full ladder. Like lots of Polish workaholics I knew of, he didn’t complain or consider reasons why he couldn’t do something – he simply got on and did it.

Uncle Karol – my Father’s Elder Brother

The following is a recollection from my Uncle Karol, to his daughter Sophia (my cousin). “While on the journey to Siberia, the train stopped at a station where I was told to get off and collect some food. Without any prior notification, the train set off and I had to run to catch it up. When I reached the carriage where my family was, I jumped onto a step and clung onto an outside rail. A Soviet guard was seemingly bemused by my efforts and repeatedly struck my hand with a spade, in an attempt to make me let go, this continued for an agonising period. I clung on through the pain because I knew that if I fell off the train, alone in the depths of Siberian forests, I’d face certain death. The guard eventually got bored of hitting me, enabling me to clamber back into the carriage.”

The Leek Polish Connection Facebook Group

I learned of a Facebook group focussed on the Leek (Staffordshire) Polish community. This fraternity was formed following a resettlement program, shortly after World War II.

Vera Wozny

In May 2023, my sister Susan and I helped produce the following video commemoration of our late mother’s life.